Justifism quiz answers

answers

The

An imperfect score invites us to learn more

The more one sees law enforcement as protecting their personal security and property rights, the more one tends to overlook the many examples of state overreach by law enforcement. The means for maintaining law and order are more easily overlooked if the results for them do not seem all that bad.

In contrast, the more one personally experiences state overreach throughout this process–from police profiling to post-conviction collateral consequences–the higher one will likely score on these items. Experience can be a painful teacher.

Justifism stems from overgeneralizing our convenient categories. No one is literally a “good guy” or “bad guy.” But first responders rely on this convention to make quick life-and-death decisions.

Once that purpose gets served, law enforcement can either humbly realize these categories serve little to any purpose in the long run.

No one is completely guilty or completely innocent. No one is perfect, nor too imperfect to exist.

The accuser can easily become the accused if reckless in their accusations. The defendant easily becomes the plaintiff if their rights get violated. The needs of the offender exist equally with the needs of those violated, and ignoring these needs tends to perpetuate the problems the judicial system ostensibly serve to alleviate.

When pursued as if these categories accurately reflect reality, pathology sets in. Our nature-based needs understandably refuse to submit to our conventionalities. Nature could care less about our shared or private beliefs. Reality occurs even when our beliefs catch us looking the other way.

From due process to actual outcomes

1. Police who pull you over for a traffic infraction never look for another reason to arrest you. FALSE

It is the police officer's basic duty to maintain law and order. Even during "routine" traffic stops. Once they spot a visible infraction, like an improper lane change, it provides them "probable cause" to search for less visible violations of law and order. For example, they may say they smell alcohol or marijuana and ask you to step out of the vehicle and search your vehicle. A routine stop can easily escalate to an arrest, and perhaps conviction. This is why it is important to know your rights when pulled over by the police.

2. Police cannot arrest you simply because you are being disrespectful to them. FALSE

While you may have a First Amendment right to free speech, and can prove no law was violated by how you disrespected a police officer, the officer still retains discretion to arrest you. To the officer, it is not so much about seeking to convict you of something as it is to fulfill their duty of maintaining law and order. You may not receive any charge if it doesn't escalate into resisting arrest or other violation. But you may find freedom does indeed come with a price.

3. Police must read your rights whenever they arrest you. FALSE

The context in which officers must read you your Miranda rights continually changes, often adjusted by case law. Currently, the only time an officer will read the Miranda warning is when they intend to ask you questions after they arrest you. This is one reason why they ask you first as a "person of interest" prior to an arrest, appealing to your feeling that you should have nothing to hide. It is best to decline to answer their questions and then ask, "Am I being detained or am I free to go?" Otherwise you are in effect waiving your rights.

From due process to actual outcomes

4. The judicial process is based on scientifically established methods. FALSE

Contrary to the scientific method, the adversarial judicial process actively resists science, such as only seeking evidence to support their preferred theory. Instead of checking for confirmation bias—an important element in the scientific process—the judicial process relies on built-in biases of “expert authorities” and forensic science to exploit the “authority” of scientific weight. Despite their popular depiction in TV shows, the National Academy of Sciences issued a stinging critique of many forensic science practices—many resulting in wrongful convictions.

5. When interrogating you about a crime, police may not use deceptive methods. FALSE

One of the jobs of cops is to get information out of people, and they usually don't have any scruples about how they do it. Cops are legally allowed to lie when they're investigating, and they are trained to be manipulative. The only thing you should say to cops, other than identifying yourself, is the Magic Words: "I am going to remain silent. I want to see a lawyer." But if you outright lie in an attempt to hinder or prevent the investigation, you may be arrested for obstruction of justice. Lying to a police officer is generally a misdemeanor crime.

6. Only someone guilty of a crime could ever be coerced into confessing to it. FALSE

Defendants may be subjected to endless hours of interrogation that wear down their defenses. Interrogators may lie and claim they already have corroborating evidence or lie and claim a codefendant or witness already implicates them. Such interrogations may use good cop bad cop tactics to intimate defendants. In desperation to avoid further “torture,” defendants will be to tell their “captors” whatever they want to hear. Youth are especially vulnerable to such tactics.

From trial to conviction

7. Accepting a plea bargain is indicative of probable guilt. FALSE

Defendants are routinely coerced, from their court appointed defense attorneys, to plead guilty to lesser offenses under threat of heavier penalties. Even when it is obvious they are completely innocent of the charges. Defense counsel knows she does not have sufficient resources to challenge every charge with a full trial, so she depends on negotiated plea deals to quickly process her mounting case load. Conviction rates do more to reflect the beliefs and biases of law enforcement and court officials than actual criminal activities.

8. Corroborating evidence is always necessary for a conviction. FALSE

In cases where no corroborating evidence would be expected to be found, such as fondling of a child, corroboration is not necessary for a conviction. The believability of the child is often critical to such cases without any corroborating evidence, spurred on by the popular belief that children would not lie about such painfully intimate things. This has prompted some investigators, especially in the past, to knowingly or unknowingly coach a child's testimony to increase its apparent credibility.

9. Hearsay evidence is inadmissible in court. FALSE

Rule 803 in the Federal Rules of Evidence provide a long list for Exceptions to the Rule Against Hearsay. Rule 804 provides for Hearsay Exceptions for when the declarant is unavailable.

10. Prosecutors agreeing to a plea deal may unilaterally renege and pursue the harshest sanction. FALSE

The alternative to accepting a plea bargain risks harsher sentencing, creating a prisoners dilemma. Such a threat is known to coerce even the innocent to accept a lesser offense conviction. Among those later exonerated by DNA, at least 25% gave incriminating statements or false confessions.

11. Most cases go to trial and only a few end in plea bargains. FALSE

With up to 97% of criminal cases processed by plea bargaining, using coercive tactics that threaten harsher sentencing if going to trial, those with no culpability can be incentivized to opt for the lesser of two imposed evils. Simply knowing someone who was innocent lose at trial can manipulate even the innocent to accept a lesser evil.

From forensic evidence to bad science

12. Forensic labs provide impartial test results equally to prosecutors and defense counsel. FALSE

Forensic evidence is conducted by state crime labs, whose analysts sometimes provide results they presume the prosecutor expects. Independent testing of any evidence is at the expense of defendants. Postconviction testing of available evidence is not always possible.

13. Judges often qualify a prosecutor’s junk science or pseudoscience expert witness to testify. FALSE

The forensic "science" of bite marks, tire tracks, hair analysis, fire patterns, and a host of other so-called sciences are readily qualified by a judge as an official expert to testify on the behalf of the prosecution (and defense counsel that can find and afford them), despite the proper Popper falsification process and other scientific standards.

14. Forensic science frequently helps to solve cases as readily depicted in TV shows. FALSE

Dubbed the CSI effect, jurors find actual forensic science as less polished than portrayed in television dramas, sometimes resulting in acquittals. Crime lab workers are not necessarily scientists. The reliance on questionable scientific methods has prompted the National Academy of Sciences to draft a report on forensic science, to compel the forensic science community to get its house in order.

15. Forensic evidence typically provides indisputable proof of a defendant’s guilt. FALSE

Many forensic techniques—burn patterns, hair microscopy, bite mark comparisons, firearm tool mark analysis and shoe print comparisons—have yet to be fully subjected to rigorous scientific evaluation. Those that are, such as serology (or blood type analysis) are often improperly done and inaccurately presented at trial. In some cases forensic analysts fabricate results or engage in other misconduct. Nevertheless, these often lead to wrongful convictions.

From appeal to exoneration

16. Criminals regularly deny guilt as a way to selfishly avoid responsibility for their crimes. FALSE

After losing their liberty, the accused understandably goes through an initial grieving phase of denial. Only 15% persist in claiming innocence while in prison, correlating with estimates of wrongful convictions. The other prisoners generally accept responsibility for their criminal actions, but may contest the cruelty of the punishment. If a prisoner complains about the dehumanizing violence of prison and if you dismiss their pleas for justice, they are not the ones in denial. You are.

17. The role of the Appellate Court is to ensure each appealed case receives a just outcome. FALSE

The role of the Appellate Court is only to review facts of law, such as the proper interpretation for a rule of evidence for a specific trial. The Appellate Panel resists being a trier of fact, entrusting the believability of a witness or presented evidence in court to the jury. While outcomes are of concern to the Court, our jurisprudence focuses entirely on process, with little accountability for upon the Appellate or any court for actual justice outcomes.

18. Conviction Integrity Units or Review Units regularly correct wrongful convictions. FALSE

Starting in Dallas in 2007, DA's across the U.S. started Conviction Integrity Units in response to the growing number of DNA exonerations from the Innocence Project. CIUs re-examine questionable convictions and guard against future error. Their ability to effectively police themselves is a matter of debate.

19. Tougher crime laws are why crime rates have declined since the 1980s. FALSE

While empirical data shows crime rates fell since its peak in the early 1990s, research has lacked consensus as to why. Get-tough-on-crime laws are more for easing public fears than addressing actual variables resulting in crime. Many factors, and not merely tougher laws, contribute to fluctuating crime rates.

20. The national sex offender registry helps reduce the rate of sex crimes. FALSE

A 2009 meta-analysis found few studies establishing a significant correlation between sex offense registries and sex crime reduction of registrants. These laws provide more to ease people's fears than improve public safety. Registry laws were written more with the public's behavior in mind than the individual offenders' since convicted sex offenders recidivism rates are much lower than widely believed and fail to account for the diverse ways sexual assaults are reported and processed.

Continuum of modalities for justifism scores:

While not a rigorously scientific measure, you can use this as a kind of litmus test to make sense of your score.

0-19 threatening justifism

20-39 severe justifism

40-59 significant justifism

60-79 modest justifism

80-100 little to no justifism

Another way to qualify your score, consider the following:

just-skeptic: slow to accept established norms of the adversarial justice, and frequently questions them; may identify as an abolitionist.

person presenting justifism: one who has accepted many established norms of adversarial justice, but when presented with their shortcomings tends to be open to viable alternatives.

justifist: one who arrogantly asserts there is no foundational problem with adversarial justice, nor any minor problems that can’t be fixed with a little reform; easily dismissive of viable alternatives, and often presents a Sinclairian conflict to interest.

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!" - Upton Sinclair

latent justifism: accumulated misconceptions about adversarial justice and the criminal justice system, malleably corrected when faced with information to the contrary of beliefs. (person presenting latent justifism)

manifest justifism: defensive about attacks on criminal justice system, indicating bias overlooking criminal justice shortcomings and low empathy for accused. (manifest justifist)

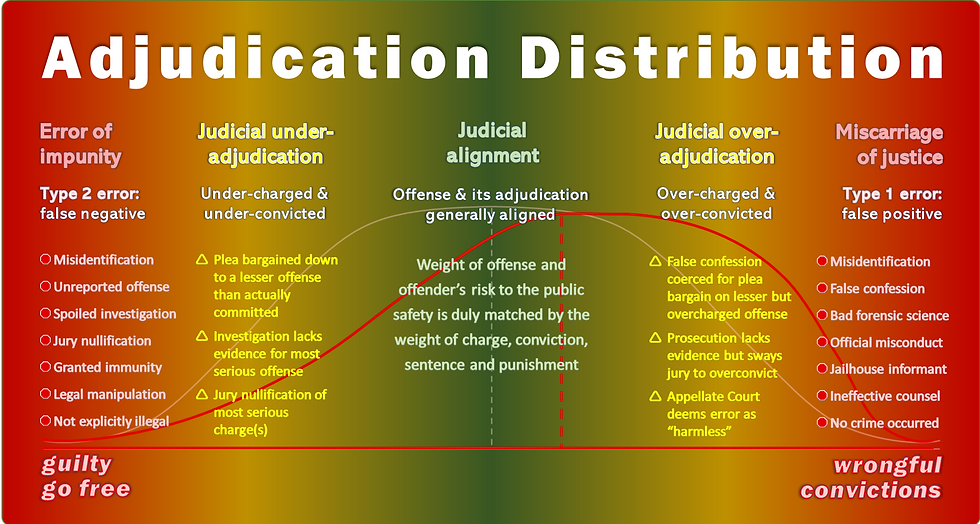

Actual outcomes of the criminal judicial process - skewed curve